• ARTLIFE NEWS • ART & CULTURE

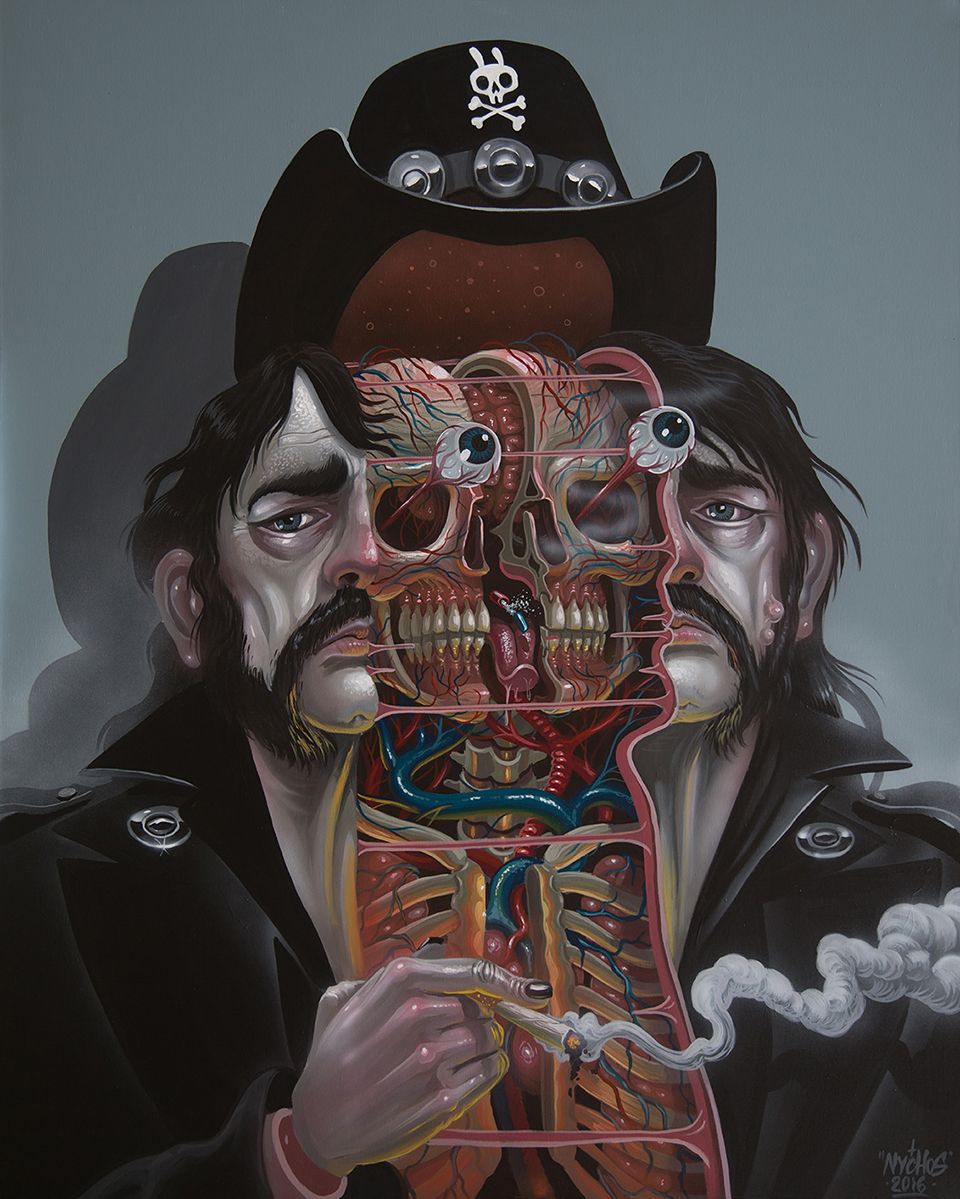

Art And Anatomy: Exploring Who We Are And What We're Made Of

Anatomy art

Ready to Start Your Collection?

Success in this market hinges on insight and access. ArtLife delivers both. We source investment-grade prints and blue-chip canvases that build real portfolio value. Contact ArtLife today to access our private inventory and acquire your next asset.