• ARTLIFE NEWS • ART & CULTURE

Jean-Michel Basquiat – The Artist Who Broke Barriers

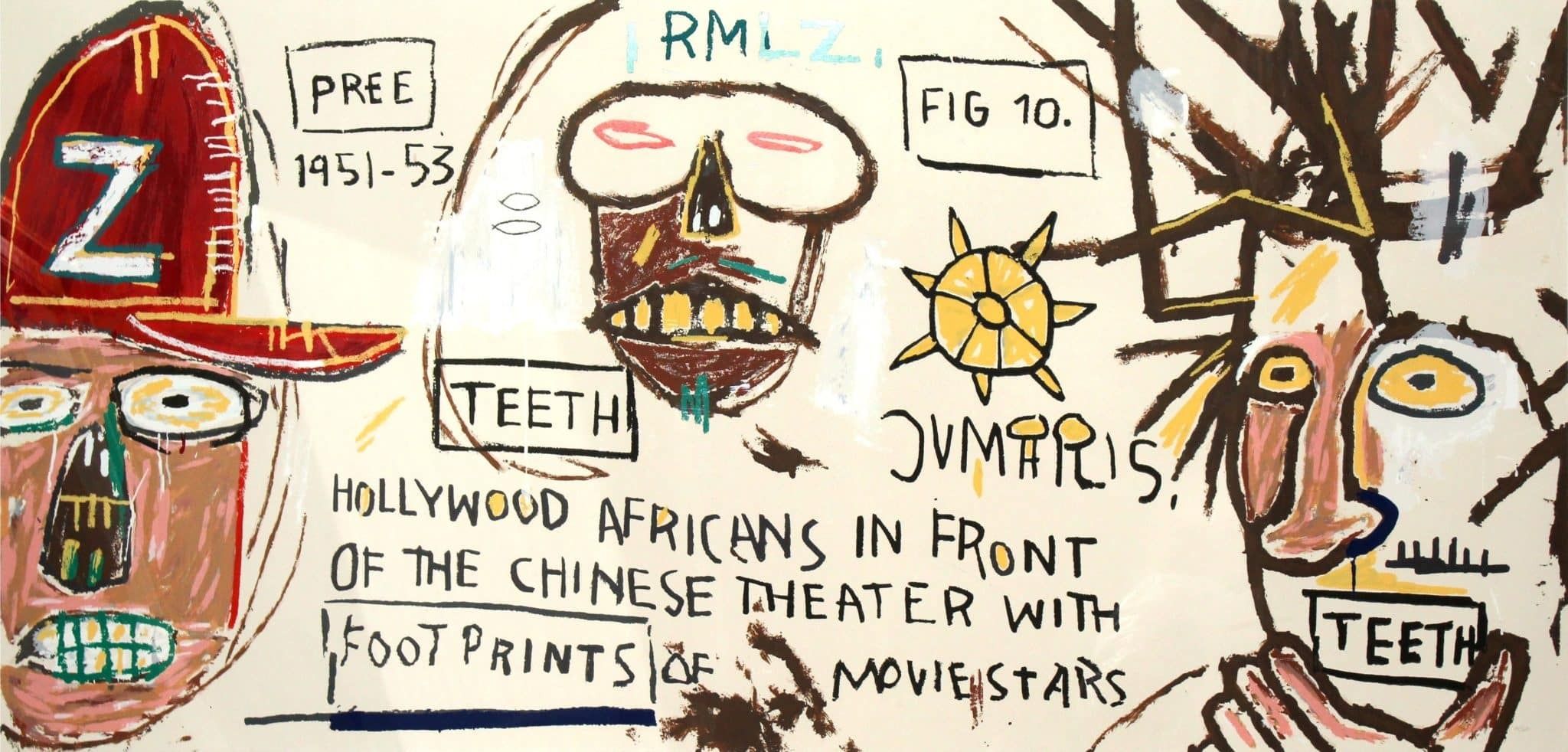

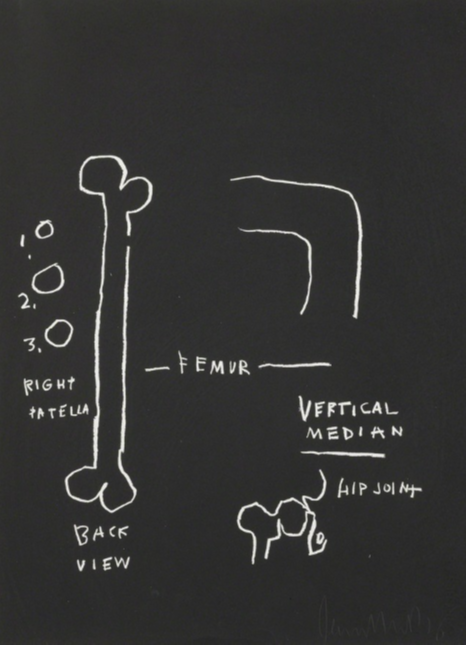

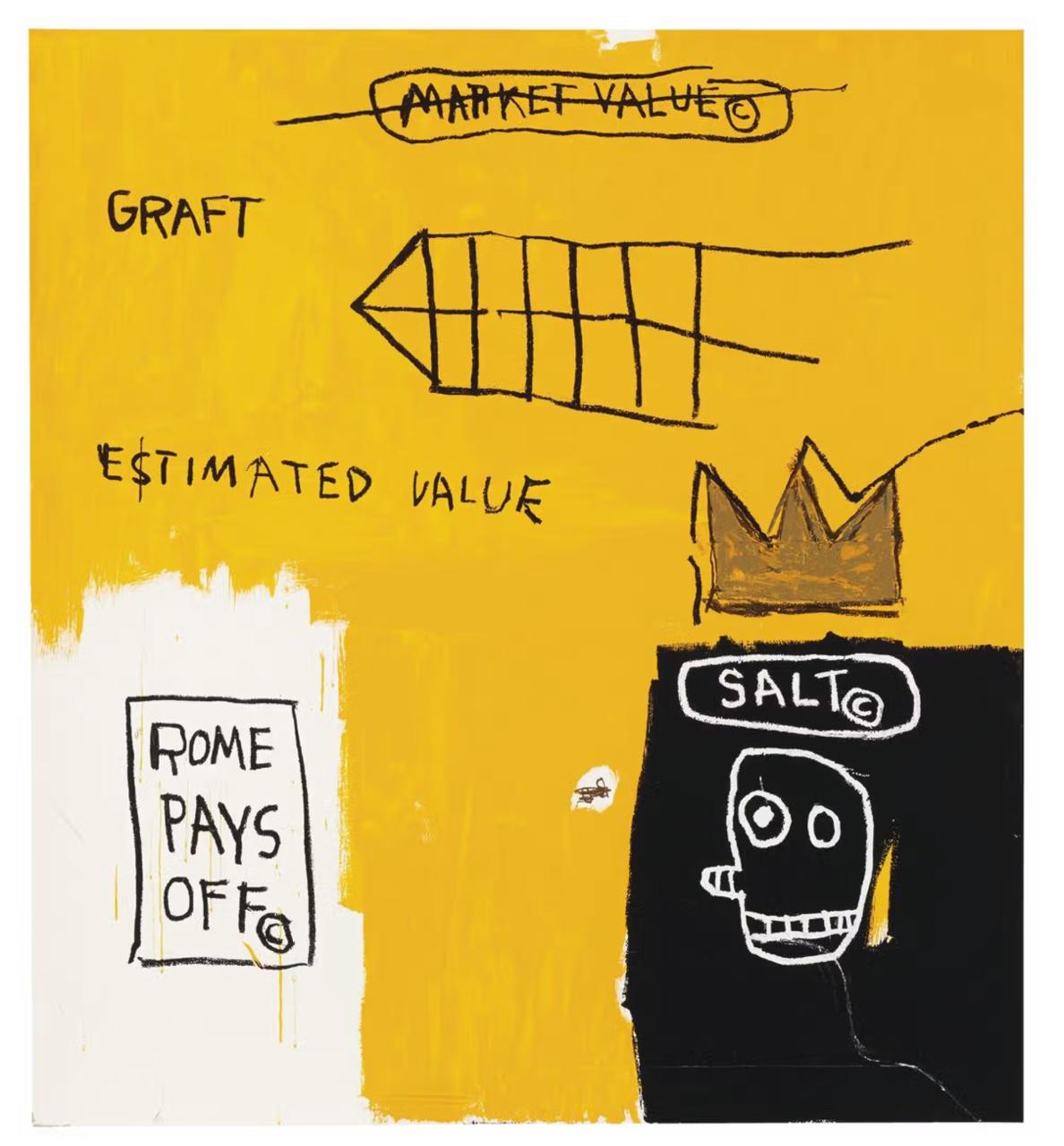

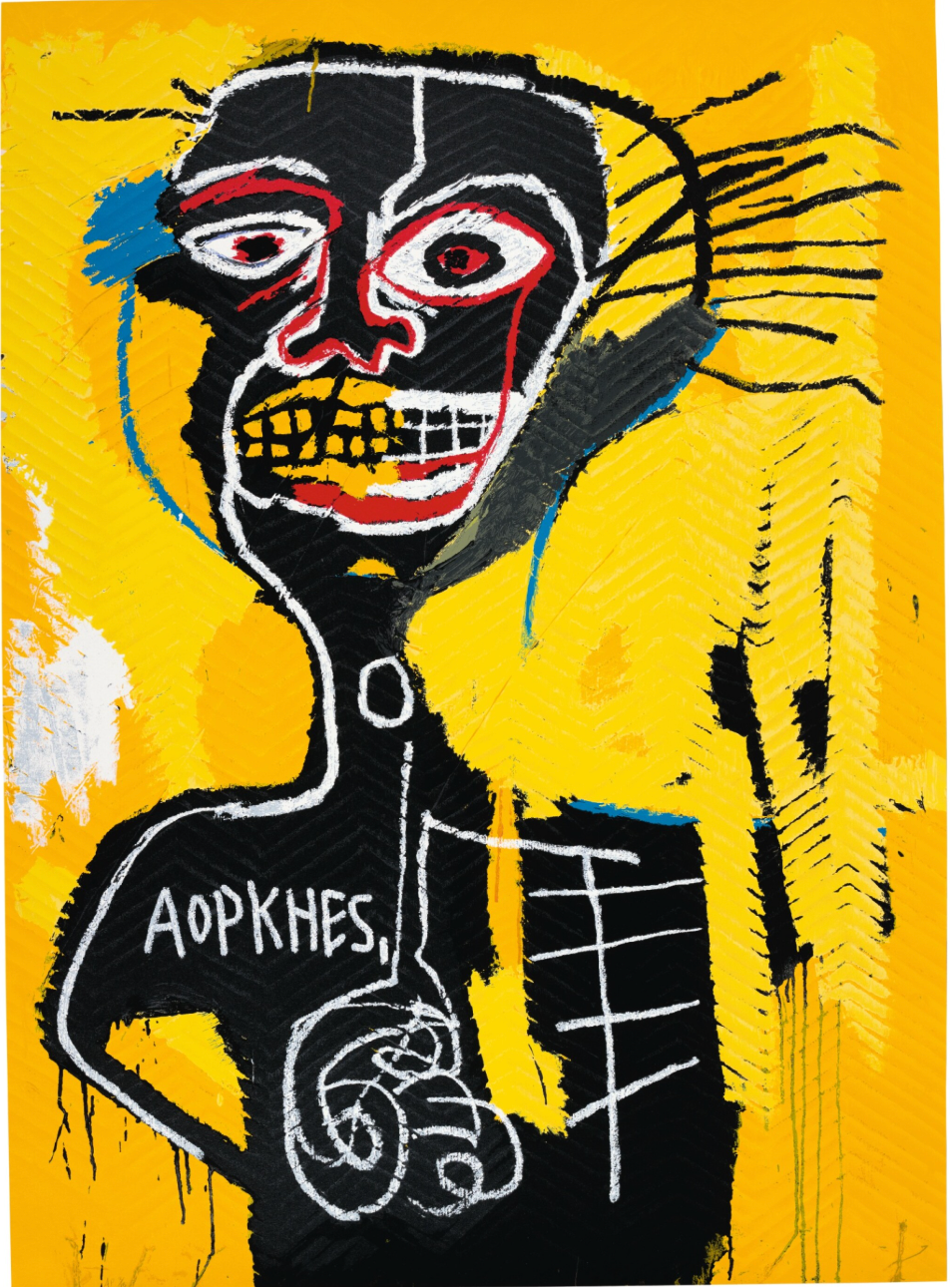

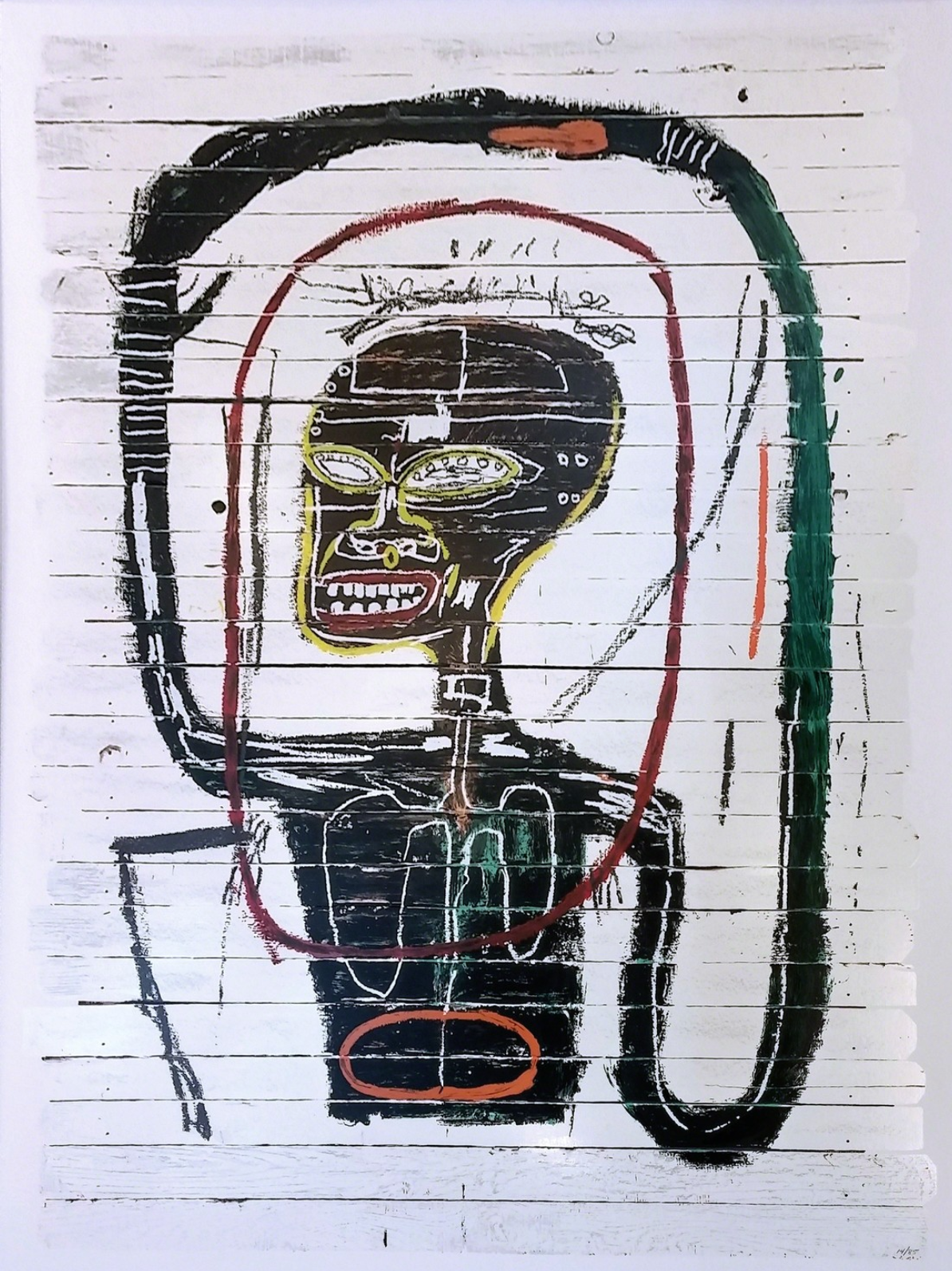

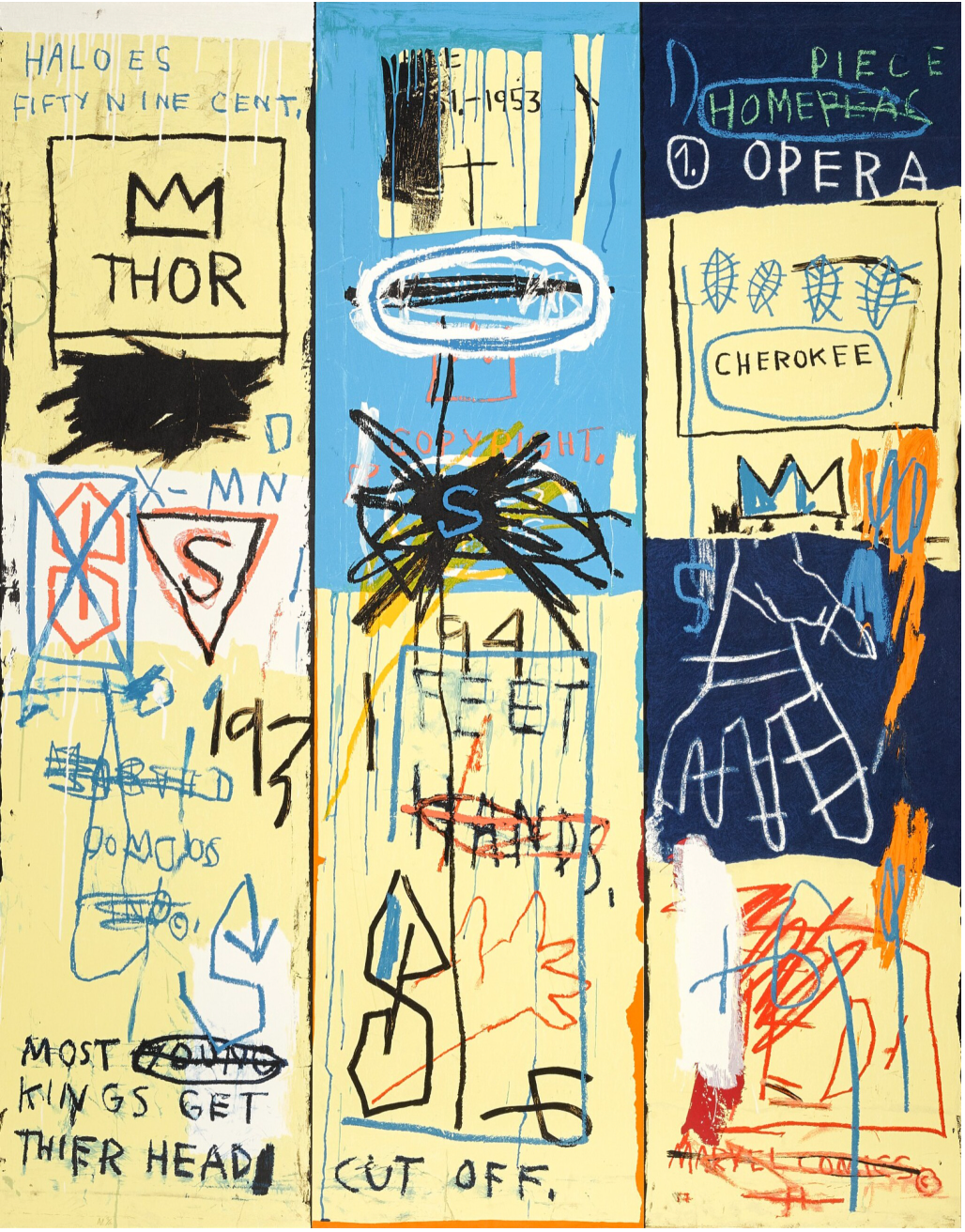

Jean-Michel Basquiat's artwork

Ready to Start Your Collection?

Success in this market hinges on insight and access. ArtLife delivers both. We source investment-grade prints and blue-chip canvases that build real portfolio value. Contact ArtLife today to access our private inventory and acquire your next asset.