Frédéric Bruly Bouabré

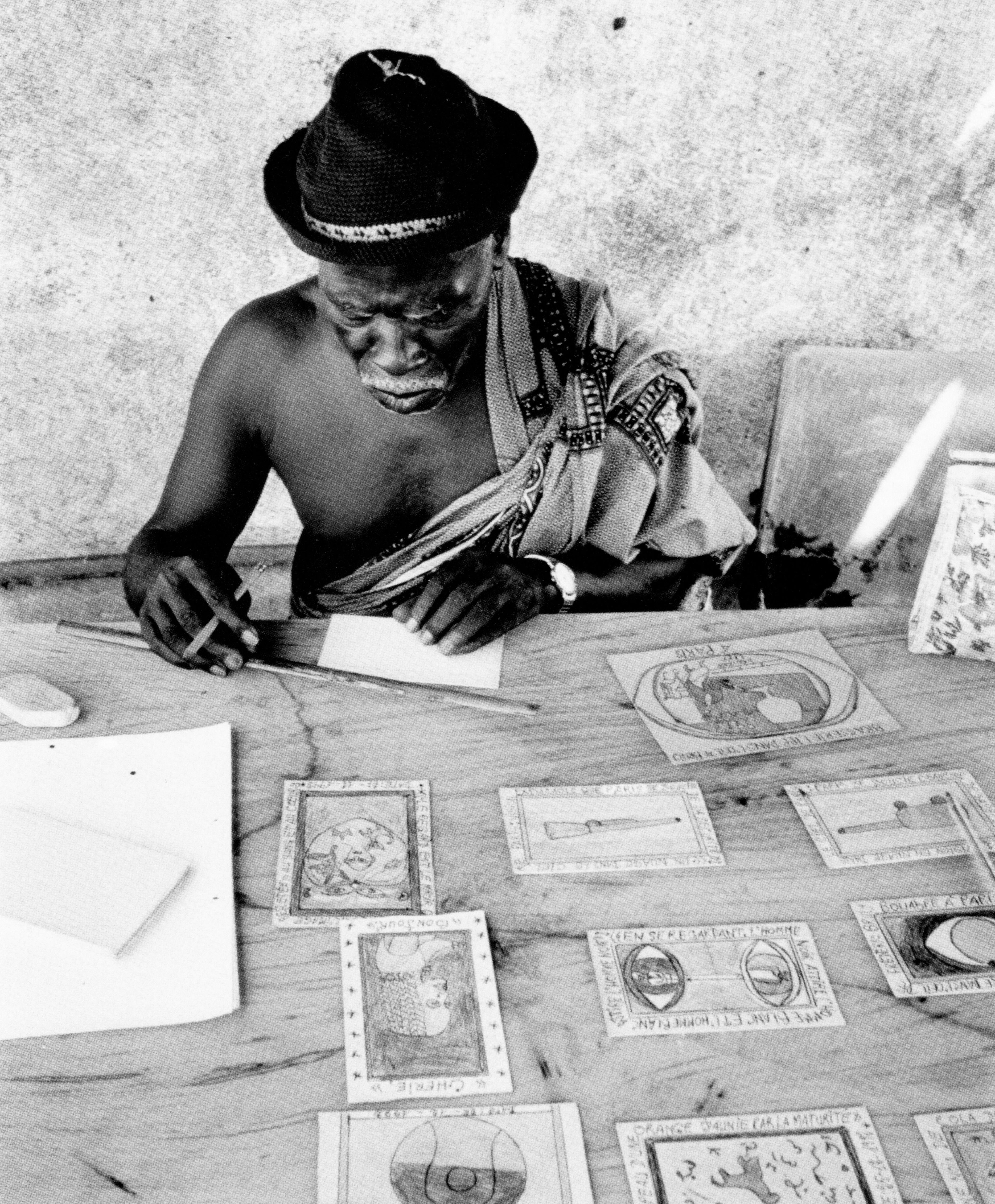

For Bouabré, his drawings are a representation of everything that is revealed or concealed — traditions, signs, divine thoughts, dreams, myths, the sciences — and he views his role as an artist as a redemptive calling. Made with ball point pen and colored pencil on recycled card stock, Bouabré used commonplace materials to produce unique iconography, often inscribing in French handwritten comments and titles along the periphery of each card.

Artwork

Exhibitions

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré

Biography

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, also known as Cheik Nadro (Zépréguhé, Ivory Coast, March 11, 1923 - January 28, 2014)

Bouabré was born in Zépréguhé, a self-taught artist, not only known for his visual creation, but also thanks to his contributions to other cultural fields, such as poetry, philosophy, and essay writing.

He not only undertook a philosophical research into African reality and the meaning of life, he started to transfer his thoughts to hundreds of small drawings in postcard format, using a ballpoint pen and color pencils. These drawings, gathered under the title of Connaissance du Monde (World Knowledge) , form an encyclopedia of universal knowledge and experience.

Creator of the writing system for his etcnic group Bété people, Alphabet Bété, an alphabet made up of 448 monosyllabic pictograms intended to establish a connection between the European and African cultures.

For Bruly, his drawings were a representation of everything that is revealed or concealed — signs, divine thoughts, dreams, myths, the sciences, traditions — and he viewed his role as an artist as a redemptive calling, Searching for a way to preserve and transmit the knowledge of the Bété people and of the world.

His work reached international recognizition at the exhibition “Magiciens de la Terre” at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, France in 1989, an exhibition that opened the doors to African artists.

Start Your Frédéric Bruly Bouabré Collection

Looking to acquire a Frédéric Bruly Bouabré? ArtLife Gallery provides curated access to investment-grade canvases, works on paper, and prints. Connect with our specialists to explore available works.